WHENEVER there is an in-depth discussion about motorcycle design past and present someone is bound to bring up the 1920 ABC transverse horizontally opposed twin. For over 50 years it has been held up as a yardstick of what might have been ... if. A lot of ifs. If the makers had been geared up for motorcycle production ... if it had been taken up by a firm like Triumph ... I nearly wrote BSA before realizing that BSA were late arrivals on the motorcycle scene and Triumph had a clear lead.

If motorcyclists had had more faith and saved up (because inevitably it was expensive) for this super bike instead of buying the mixture as before, which was likely to be a simple side-valve single in a glorified bicycle frame.

The ABC enthusiast lobby winds up the argument by pointing to the BMW as the direct descendant of the ABC. Personally, I think the connection so tenuous it is wrong to infer that the sales success of the BMW . . . only in the last decade or so, it should be remembered has anything to do with the fact that BMW took up the ABC layout in the middle 20s and eventually refined it into a machine which could take the world's fastest record and win our most prestigious race, the Senior Isle of Man TT.

Given the length of time, the amount of State funding and the determination fed by national pride, I think the Bavarian company could have achieved the same results, or even more perhaps, with other layouts.

Surely it comes down to what I state in the first line of the road test. Success is having the right product at the right time.

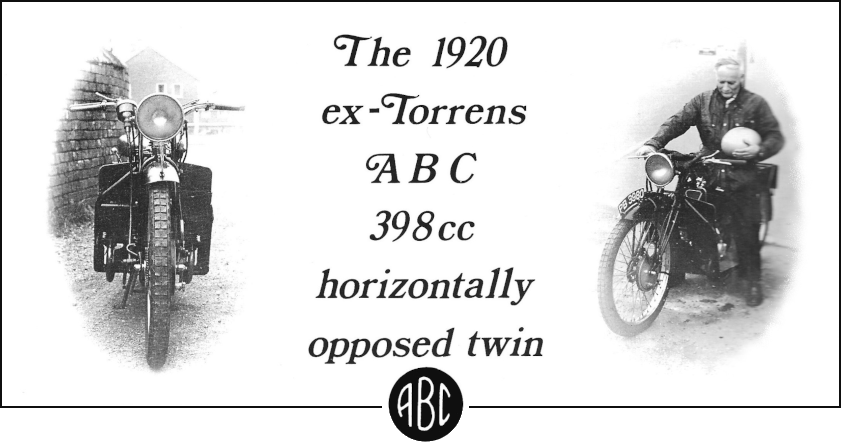

The 11th ABC to be produced. Once owned by Torrens of "The Motor Cycle". Performance and general feeling of this flat-twin have much in common with LE Velocette ways. It arrived on the motorcycling scene at least 10 years too early for success with another design which Britain discarded! No kickstarter is fitted, but the docile, low-compression engine comes to life very easily when the bike is paddled off

Even for BMW the right time did not come until a new type of motorcyclist appeared — the executive type, for want of a better term — who had money to indulge in a new type of motorcycling long-distance main road and motorway touring. I have an idea it was Honda with the "you meet the nicest people on a Honda" advertising that helped to start this new motorcycling interest. The flat-twin BMW happened to have the long legs and other attributes for this kind of work. And a very expert marketing organization went into action to ensure that the "nicest people" rode BMWs.

We shall see if they achieve the same market

In holding up the BMW as the example of what might have been, the ABC enthusiasts do, I find, tend to forget the post-war Douglas which with its chain drive and original springing was a more obvious descendant.

Its market failure, despite a tremendous effort by the Bristol firm which encompassed trials and clubman racing, proved if nothing more that it

was not the right product at the right time ... if any time. Likewise the Velocette Valiant which you could say was an attempt to make a baby BMW. Even BMW's baby, the 500, seems to have been a failure marketwise. Of course by the "right product" I mean the product the average motorcyclist wants. It seems he still wants a bike that looks more or less like the one he had before but certainly it has to look a bit like the bikes that win races, scrambles, enduros — in general layout if not in outward appearance. I left the other transverse twin mini super-bike, the LE, till last because it was to me the worst example of the wrong product for the market.

It was a little beauty designed with infinite care by dedicated engineers for the man in the street market but the man in the street did not, could not, appreciate that. He settled for a BSA Bantam until such time as he could afford a car or perhaps went to a scooter where he could not see the works. Then Soichiro Honda got it — the C100, C50, really right with the Cub series — and sold millions.

The ABC is another of the tragic attempts to give motorcyclists what the designer thought they ought to have without finding out what motorcyclists really wanted ... outside the correspondence columns. At two ends of the market George Brough eventually settled for making what he knew they wanted rather than what he thought they ought to have. And Edward Turner really got it right with his Speed Twin after getting it wrong with his four.

TITCH ALLEN

After a brief ownership of the ABC, Torrens bought a flat-tank side-valver, a 16H Norton. You could not get more old fashioned than that. He kept that until the early 30s when he transferred his enthusiasm to an ohv 350 Levis.

On paper, it was — and is — difficult to fault Bradshaw's ABC

SUCCESS in motorcycle manufacture demands the right product at the right time. Some makers have failed through not keeping up with opposition; some because they were too far ahead.

The transverse twin ABC of 1919 was born at least 10 years too soon and failed. Even now dedicated followers still wait for its reincarnation though its half-cousin, the LE Velo has come and gone. Only the lordly BMW, a direct descendant, continues to vindicate the basic principles.

Perhaps if the ABC's foster parents had been in the motorcycle business the story would have been different. The orphan might not have been abandoned when the financial snowstorm fell.

Granville Bradshaw, one of the most brilliant designers the industry has known, designed the ABC to keep the wolf from the door of the Sopwith Aviation Company when war contracts ceased.

It is said he did the drawings in 21 days, some part of that time in his favourite creative spot, a bath full of warm water with his drawing board above.

It looked a world-beater. The specification of over-square ohv transverse-twin with unit four-speed gearbox, duplex built-in crash-bar frame, rear springing and dynamo lighting. All that is not outdated today. Imagine the impact when the norm was a single-cylinder sidevalve, belt drive, rigid frame, gears if you we’re lucky, and gas lights.

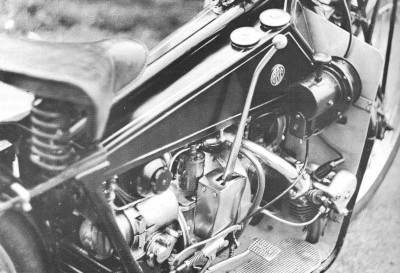

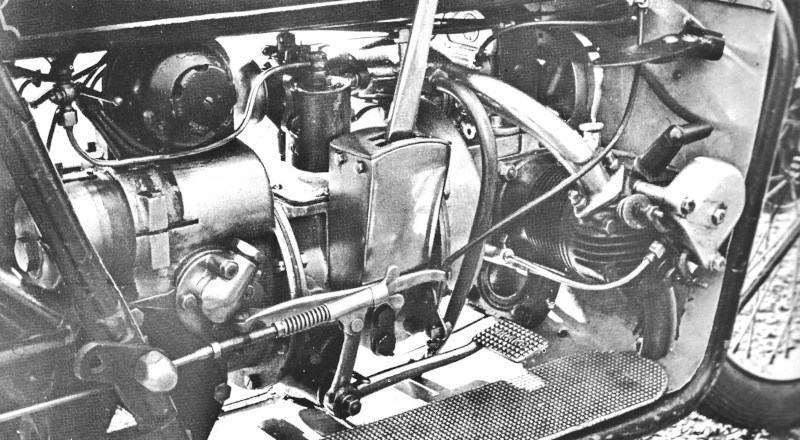

Enclosed rocker gear and alloy pushrods were advanced features; car-type transmission and gate change for the four-speed gearbox were distinctive too.

Sopwiths knew how to make airplanes but it took them a long time to get into motorcycle production and overcome teething troubles. It was not until they got Walter Moore in did they really start to move, the same Moore who designed the first cammy Norton. In 1923 the baby was three years old, Sopwiths had spent the sum allotted for its upbringing, and it had been pay, pay. pay, with no profit. The directors, lacking the faith or the folly of dedicated motorcyclists, wanted out.

Gnome Rhone, the French aero engine firm, adopted the ABC and carried on for a while. In Germany the BMW concern liked the layout, added shaft drive and a pressed steel frame and that avenue of history began.

But by this time the full order book had wilted. Bike-hungry customers had settled for something less exotic and more available. The price had rocketed from the original unrealistic £100 to a more viable £160 — for which you could buy three normal 350s!

Teething troubles mostly concerned the rocker gear, prone to shed the push rods.

Accessory firms soon offered conversion kits which overcame that. Not particularly quick in standard trim, say 60 mph, the high-revving well-balanced little twin was open to tuning.

Emerson, the development engineer had the sauce to take the 500 our record at over 70 mph. Private owners scooped short-distance events.

On paper it was — and is — difficult to fault the ABC. The swinging-fork rear suspension was well thought out, the pivots wide spaced, not too far from the final-drive centre, and stiffened by the rear-carrier mudguard-stay complex which formed the rear anchorage for the leaf springs. Bradshaw anchored his leaves rigidly at both ends, avoiding shackles and forcing them to bend in a flattened S formation, which increased the rate and inherent damping.

At the front the normal girder fork used a quarter-elliptic leaf spring.

From his experience in designing aircraft engines Bradshaw chose steel cylinders with very thin, turned-from-the-solid cooling fins. His rocker gear, if not wildly successful allowed plenty of cooling for the cylinder heads. The lengthy induction pipe from the single-lever carburetter (a Claudel Hobson) was heated with exhaust gas.

Against a background of staccato singles the ABC was a crowd stopper, like the first LE Velo. It had no staccato bark. Just made a whirring sound. The engine was by no means silent mechanically but the noises were so small in volume and so numerous as to be indefinable.

Rocker gear apart, it was reliable enough given mechanical sympathy; it was too fragile for the heavy handed, but they did not buy them anyway...

One has no need to speculate on the motivation behind the then staggeringly unconventional design of the ABC. It is clearly, if somewhat long windedly, set out in the original catalogue. I will cut it as short as I can:

"The intention ... has been deliberately to break away from the tradition which has hitherto resulted in the self-propelled two-wheeler remaining a lineal descendant of the pedal bicycle. The conditions under which a motorcycle is ridden are entirely different from the pedal machine, with the sole exception that the stability of the whole is under the rider's control.

Hence pedal cycle influence has never been exerted to any useful purpose; on the contrary it has prevented motorcycle design developing...

The ABC materializes the conviction that the only sound motorcycle is in essentials a two-wheeled car."

No kickstarter is fitted, but the docile, low-compression engine comes to life very easily when the bike is paddled off.

The market for an "ideal" machine is always small. Pundits propound and doodle "ideal" specifications and have from time to time persuaded manufacturers to produce such machines. History is littered with the skeletons of them. Voluble and persuasive the enthusiast may be, but when the first machines reach the showroom he is loath to find his cheque book

"Better wait a year or so and see how they perform" he says, this just at the time when the manufacturer needs encouragement.

So I fear it would have been with the ABC even if it had gone into big production. The untapped market of the man in the street is elusive and has futilely mesmerised some of the best brains in the industry. The Japanese have come nearer seizing it in their grasp than anyone, not by making machines of "ideal" specification but by sophisticating basically simple designs.

The ABC engine has intriguing features. To permit a one-piece crankshaft, the big-end eyes are large enough to slip over the crank throws, the roller bearings being poked in afterwards and retained by split collars clamped on to the journal'. The light-alloy pistons have concave crowns and are extremely short. Someone took an awful chance over the lubrication system, relying on crankcase depression to persuade oil through an adjustable drip feed. The hand pump is for "special circumstances" according to the instructions.

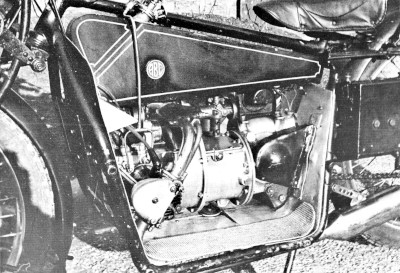

I understand that the Bradshaw prototype has a proper mechanical pump built in and that it was jettisoned in an attempt to cut cost. The test machine featured here had been fitted with the Best & Lloyd semi-automatic hand pump and sight feed, that mainstay of manufacturers in the early Twenties. Other mods incorporating period goodies are the straight-through exhaust system replacing the standard transverse silencer, proprietary rocker gear with light-alloy pushrods (my ABC expert Bob Thomas guesses this is a Taylor-Young conversion) and special finned brake drums, the front being the same size as the rear (a works mod this as used on their 1920 "TT entries).

The test machine is specially interesting because it is an early one, the 11th off in 1920 (only prototypes were made earlier) and was owned in 1926 by the illustrious Arthur Bourne, later Torrens of The Motor Cycle and father figure to a generation of motorcyclists. That may be why it incorporates a number of works and contemporary mods.

Legends of unreliability in service are completely dispelled by the fact that Walter Green's sons have covered many thousands of trouble-free miles and even took their driving tests on it! So, given sensible use and maintenance, the ABC was reliable enough. But being so vibrationless and silent it asked to be over-revved by the clueless. Even the valve pushrods stayed put if valve springs were changed regularly and the tappet adjusters were no screwed out to the point when there was no cup left in the rocker to keep the rods in place.

The slightly sporty burble of Walter Green's special exhaust nicely drowns any mechanical noise from the engine unit and the enclosed rockers must help too. I am afraid there was oil in the front brake so it was pretty useless and even the rear one was not as good as the cooling fins suggested it might be.

The 11th ABC to be produced. Once owned by Torrens of "The Motor Cycle", it incorporates a number of modifications.

Steering of an ABC — or most of the ones I have ridden — is a bit peculiar. At walking speed, it is self-willed or too positive; there seems to be too much head angle so the steering head lifts and falls going from lock to lock. Tricky at first but something one gets used to.

The impression, and it is confirmed by my expert friend, is that although not all ABCs steer like this, the ones that do also steer better at speed. I believe it. At all speeds I was able to reach the steering was very positive and the rear springing worked like a charm. Bradshaw's trick of anchoring leaf springs rigidly at both ends and his dictum about no-loose-shackle really works.

You can feel the self-damping action of the leaves in the restrained and slightly delayed rebound. (Pity the Hitler War stopped development of a big Panther with this Bradshaw leaf springing.)

No kickstart on the test machine you will note and no loss. Like a little Douglas, the ABC, with its low saddle, can be paddled off with small effort. There's no mention of a kickstart in the original catalogue and the one which appeared on later models was troublesome.

It is difficult when riding the ABC to avoid comparison with the latter-day LE Velocette.

Performance is about the same as the 200 cc Velo and there is the same slightly unreal quality of drifting along with a whirring noise and no vibration. Plus the same feeling of safety imparted by a frame-legshield and an engine assembly which is obviously going to take the brunt if you fall.

One of the best features of the design is the four-speed gearbox and engine-speed clutch.

The box is very robust and would handle twice the power output. Though of crash type, it changes easily with the long, hand lever. In fact the gears can be swapped as fast as the lever can be moved, this without any double-declutch technique. The clutch, which has a single metal plate trapped between fabric faced ones, is light and frees cleanly. The bevel and pinion which turn the drive to the final chain are hefty enough for a small car and no trouble need be expected there, especially as there is a rubber-cush in the rear-wheel sprocket.

Specification

Engine: 398 cc ABC aircooled transverse horizontally-opposed twin-cylinder fourstroke.

68.5 x 54 mm bore and stroke. Detachable cast-iron ohv heads on steel cylinders.

Lubrication: Constant-loss utilising crankcase depression. Sight feed on tank top.

Ignition: Gear-driven magneto above engine.

Carburation: Claudel Hobson instrument.

Exhaust-heated inlet manifold.

Transmission: Flywheel clutch and four-speed gearbox in-unit with engine. Car-type H-gate hand gear change. Bevel-drive to rear chain.

Frame: Duplex cradle splayed to embrace foot- boards and protect engine cylinders. Pivoted-fork rear suspension with leaf springs, Girder front forks with leaf spring.

Wheels: Beaded-edge rims for 2½ x 26in tyres. Internal-expanding brakes.

Tanks: Combined petrol and oil tanks. Capacities approximately 2¼ Imperial gallons of petrol and two pints of oil.

Dimensions: Saddle height, 28in. Handlebar width (for touring bars), 26in. Weight, 243 lb.

Original finish: All black enamel, including tank, wheel rims and handlebars. Small parts and brake plates nickel-plated.

Performance: For production model

Third: 40 to 45 mph.

Bottom: 15 to 20 mph.

Petrol consumption: 60 to 80 mpg.

Maker's claimed output at rear sprocket was 8 bhp (continuous rating).

To sum up:

The ABC is the ultimate in collectors' pieces, suitable for the engineer enthusiast who wants something truly different for road-going display only. Granville Bradshaw's design is most certainly not sporting in character.

Restorer's note: Several features of the test machine differed from the production machines.

The improved after-market rocker gear has been mentioned, likewise the finned brake drums ... the front larger than standard. The handlebars and controls are obviously of more recent date, likewise the saddle. The "go fast" exhaust system is typical of the mods owners made to their machines, even vintage enthusiasts, before the "restore it to catalogue" cult took over. I remember Torrens telling me with pride of the modifications he had made to this and other machines in the vintage years. When Walter Green restored it he set more store on making it a nice bike to ride rather than a show machine.

This is another in a series of occasional articles based on reports which originally appeared in the 1970s in the Vintage Road Test Journals.

They have been adapted, with new material added where appropriate, by the author, C.E. — Titch — Allen.