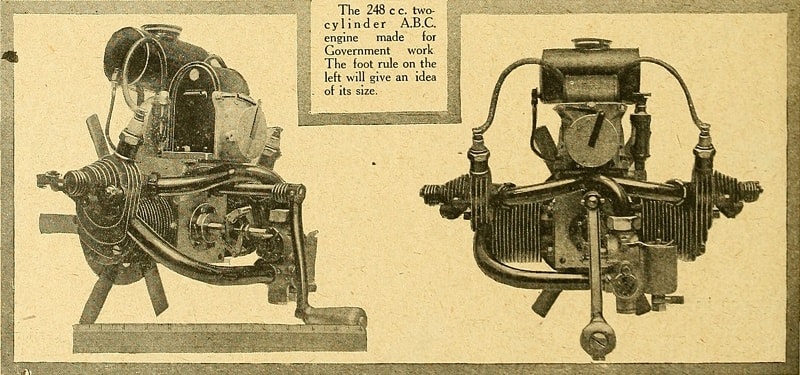

Details of a Remarkable High-speed Engine built by the A.B.C. Company for Government Work.

"Road Rider's" Impressions.

Finding myself in the Hersham district the other day, I called in at the A. B.C. works and spent a most interesting hour with Mr. Granville Bradshaw. I am afraid it will disappoint many enthusiasts to hear that the output of A.B.C. motor cycles, as with many other British makes, is almost entirely suspended. The research work in connection with the 1916 models is proceeding in odd moments, as a preparation for calmer days, and I saw the experimental engines and frames (now far advanced towards perfection) of the famous Model C, which is expected to do 90 m.p.h. on Brooklands, and weighs no more than lb. all on.

A Really Lightweight Engine.

As I walked about the toolshops, I became increasingly conscious of an earsplitting uproar outside.

Oh, that is our new lightweight!" I went to investigate, and discovered a horizontally-opposed steel cylinder twin, 60 mm. x 44 mm. , undergoing a six hours' test in the open air. With a fan brake attached it was running at over 4,000 r. p.m. and developing over 4 h.p. The entire power unit weighs no more than 23 ¼ lb., of which the magneto scales over 7 lb. and the automatic Claudel-Hobson carburetter very nearly 2½ lb. The absence of vibration is so extraordinary that if a finger is pressed on the magneto at high rates of r. p.m. it is difficult to determine by touch alone whether the engine is running or not. This 23 lb. outfit is employed for starting up huge engines on seaplanes, airships, and motor boats, and replaces far more cumbrous alternatives; in fact, the lightest engine starter yet applied to such purposes (an electric dynamo) weighs nearly four times as much. What a fascinating baby bicycle could be rigged up with this delicious little engine, the workmanship of which is absolutely superb!

Apart from the experimental 1916 models, the only cycles coming through were a few spring-framed machines ordered by the Government for a district where rigid frames are officially considered impracticable. N.B.—The War Office considers spring frames unnecessary in France and Flanders.

In the engine department the two-throw crankshaft of a colossal aviation engine was one of the most interesting exhibits. Imagine seven connecting rods crowded together on each of two crank pins, the length of each pin being about 5in. Yet with roller bearings these dimensions are found quite practical.

Increasing Cooling Capacity.

The big lathe turns out a completely machined cylinder for the 3½ h.p. 500 c.c. engine in thirty-five minutes, the fins being machined and the bore drilled out at one operation. This time economy renders the steel cylinder cheaper than the ordinary iron castings.

Mr. Bradshaw was very “cockahoop” over a wee discovery anent the treatment of the cylinder bore. The alteration from standard methods of finishing the bored surfaces results in the engine keeping 20% cooler, e.g., with the big aviation engines the radiator surface can be reduced to that amount, with valuable economies in weight. On the air-cooled cycle cylinders the risk of overheating is correspondingly eliminated. A very neat mechanical oil pump will figure on all models when manufacture resumes its normal round.

I have seldom visited a factory where magnificent workmanship and a high degree of technical knowledge were so happily combined, and I venture to prophesy that the A.B.C. machines will achieve a formidable reputation alike on road and track when once motor cycling settles down to routine work again.

In the meantime, the works are keeping their hand well in with the 500 c.c. air-cooled pattern, which is in great demand with the services for running the dynamos of portable searchlights, in which duty it represents a great saving of weight as compared with all substitutes. Overheating is prevented by an enormous fan, some eighteen inches in diameter, which keeps the engine so cool that twelve hour tests at full revolutions result in no injury to the bearings, and in no diminution of power output. We may, therefore, expect the road models to be better than ever when peace returns, and we may dream of a very fascinating lightweight when the 23 lb. 250 c.c. vibrationless engine makes its début in a cycle frame: Its steadiness is evinced by the fact that it does its power tests clamped in a medium-sized parallel vice laid on the ground outside the running shed!

Some engineering details of the highly interesting 248 c.c. A. B.C. engine referred to in the foregoing notes are given hereunder:

| Engine alone weighs | 14 lb. |

| Magneto weighs | 7 lb. |

| Carburetter weighs | 2¼ lb. |

| Power developed: | 2 h.p. at 2,000 r.p.m. |

| 3 h.p. at 3,000 r.p.m. | |

| 4 h.p. at 4,000 r.p.m. |

As an experiment, the engine has been run on full throttle without_ any load, and has attained the remarkable speed of 8,000 r.p.m. This is probably a world's record for a reciprocating engine.

The crankshaft is fitted with A. B.C. roller bearings, and weighs 15 oz., a complete connecting rod weighing 2 oz.

Mechanical lubrication is employed in the shape of a gear-driven oil pump, which is fixed to the crank case cover and runs at one-fifteenth engine speed.

From “The Motor Cycle”, September 30th, 1915